Chronic disease risk factors by industry

Some industries are more prone to chronic disease risk factors. Read the statistics here.

Summary table

Nationally since 2007–08 there has been positive change in health and wellbeing at work with less people smoking and drinking at harmful alcohol levels and more people who are physically active. However, two-thirds of the population are overweight or obese and only 50 per cent are eating the recommended fruit and vegetable intake.

Below is a summary table outlining risk factors amongst industries.

Prevalence of modifiable lifestyle risk factors amongst industries (%)

| Analysis of persons 18+ years | Current smoker | Inadequate fruit and vegetable intake | Physical inactivity | Over-weight or obese | Increased high risk waist circumference | Alcohol increased lifetime risk | Poor mental health |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National 2007-08 | 22 | 49 | 71 | 59 | 55 | 24 | - |

| National 2014-15 | 15 | 50 | 62 | 62 | 57 | 20 | 9 |

| Agriculture 2014-15 | 14 | 45 | 77 | 76 | 67 | 29 | 3 |

| Transport 2014-15 | 22 | 52 | 66 | 78 | 67 | 21 | 8 |

| Construction 2014-15 | 24 | 53 | 58 | 69 | 52 | 36 | 8 |

| Manufacturing 2014-15 | 18 | 55 | 69 | 68 | 58 | 22 | 8 |

| Mining and resource 2014-15 | 46 | 67 | 71 | 63 | 30 | 7 | |

| Health and social assistance 2014-15 | 10 | 46 | 64 | 61 | 66 | 11 | 9 |

| Public Service 2014-15 | 10 | 50 | 55 | 68 | 65 | 16 | 7 |

| Wholesale and retail trade 2014-15 | 16 | 51 | 65 | 56 | 51 | 18 | 10 |

| Electricity, gas, water and waste services 2014-15 | 21 | 49 | 59 | 72 | 59 | 32 | 11 |

| Education and training 2014-15 | 7 | 40 | 56 | 56 | 56 | 14 | 9 |

| Telecommunications and other services 2014-15 | 12 | 56 | 58 | 61 | 57 | 20 | 8 |

| Arts and recreation services 2014-15 | 11 | 44 | 46 | 58 | 43 | 18 | 11 |

| Other services 2014-2105 | 18 | 50 | 63 | 60 | 59 | 20 | 9 |

Shaded figures indicate percentages higher than the national average.

2014-15 National Healthy Survey: Prevalence of modifiable risk factor results for industry. Note: Poor mental health was not measured in 2014-15 National Health Survey

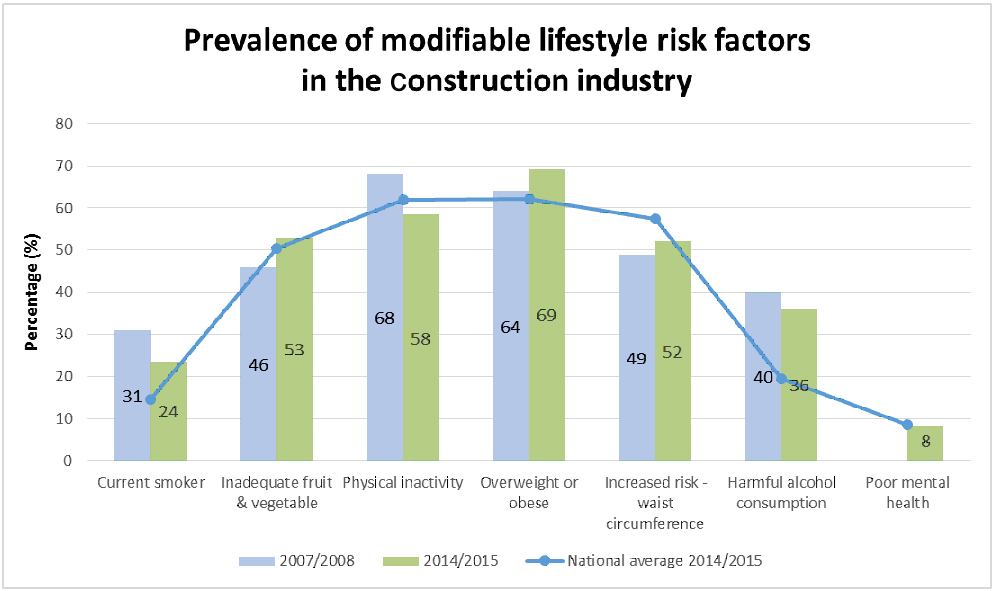

Health status of the construction industry

According to the 2014-15 National Health Survey, when compared with all other industries, construction workers have higher rates of smoking, harmful alcohol consumption, obesity levels and inadequate fruit and vegetable consumption compared to the national average. Since 2007-08 there have been slight improvements with construction workers smoking less, being more physically active and consuming less harmful alcohol levels. However, levels of poor nutrition, overweight and obesity continue to rise within the construction industry (see graph below).

Click on graph to view larger version.

National Healthy Survey 2014-15 and 2007-08: Prevalence of modifiable risk factor results for the construction industry.1 Note: Poor mental health was not measured in 2007-08 National Health Survey.

The construction industry experiences high rates of musculoskeletal injury, and psychological distress with 20 per cent of workers experiencing stress, depression or anxiety within the last 12 months.2,6

Employment in construction has grown 33 per cent in the last 11 years and is set to grow 60 per cent over the next five years.3 Construction makes up 9 per cent of Queensland's workforce making it the largest industry sector.4 This sector accounts for 10 per cent of workers compensation claims in Queensland.4

Industry factors that contribute to poor health

The construction industry faces unique challenges that may be contributing to the poor health of its workers:

- Male dominated workforce: Men are less likely to have regular medical check-ups or seek help for entrenched physical and mental health issues.3

- Long working hours: Evidence has shown workers that averaged three to four hours of overtime a day were around eight times more likely to develop certain chronic diseases.5 Construction workers have stated that long hours, insufficient recovery time, and exhaustion prevent them from participating in healthy lifestyle activities such as sport and physical exercise and attribute to high levels of alcohol use.7,8

- Transient workforce: The absence of a central workplace means workers may be unfamiliar with the worksite and have limited time available for work health interventions and safety training.

- Project-based work: Results based remuneration is common, profit margins are generally narrow, and deadlines are tight. Employee wellbeing, health pursuits and achieving a work life balance are not always a priority.

Impact of worker health and wellbeing on safety and business performance

Workers' health impacts on all parts of the construction supply network, including principal contractors, trade sub-contractors, labour hire firms and project clients. The effects of poor health in the construction industry can be seen in indicators such as injury rates and workers' compensation premiums, deadlines, productivity and skills shortages. For example:

- raised levels of fatigue and reduced alertness that affect the safe operation of plant and machinery

- reduced effectiveness and productivity of workers due to impaired physical and mental functioning, leading to project delays

- increased rate of injuries, illness and absenteeism, leading to higher workers' compensation claims/premiums and skills shortages

- accelerated health decline due to physical nature of the work, resulting in older workers with valuable skills and experience leaving the industry prematurely

- increased rate of worksite incidents and near-misses, posing a risk to other workers on-site and affecting compliance with work health and safety legislation.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2014-2015 National Healthy Survey: Prevalence of modifiable risk factor results by industry [Internet]. Canberra (AUST): ABS; 2016. [Cited 2 August 2016]. Available from: http://www.abs.gov.au/australianhealthsurvey

- Safe Work Australia. Construction industry profile [Internet]. Canberra (AUST): SWA; 2015. [Cited 19 August 2016]. Available from: https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/doc/construction-industry-profile

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Labour Force, Australia, Detailed, Quarterly, Feb 2016, cat. no. 6291.0.55.003 [Internet]. Canberra (AUST): ABS; 2016. [Cited 16 August 2016]. Available from: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/6291.0.55.003

- Queensland Government. Industry job trends and statistics. [Internet]. Brisbane (AUST): Queensland Government; 2014. [Cited 19 August 2016]. Available from: https://www.qld.gov.au/jobs/pages/industry.html

- Virtanen M, Heikkila K, Jokela M, Ferrie JE, Batty GD, Vahtera J, Kivimaki M. Long Working Hours and Coronary Heart Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. American Journal of Epidemiology [Internet] 2012; 176(7):586-596. [Cited 19 August 2016]. Available from: http://aje.oxfordjournals.org/content/176/7/586.long

- Viester L, Verhagen E, Bongers P & van der Beek A. The Effect of a Health Promotion Intervention for Construction Workers on Work-related Outcomes: results from a randomized controlled trial. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health [Internet] 2014. [Cited 17 August 2016]. Available from: http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs00420-014-1007-9

- Lingard, H., Cooke, T. & Blkismas, N. (2011) - Coworkers' response to occupational health and safety: An overlooked dimension of group-level safety climate in the construction industry? Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 18 (2), 159-175.

- MacKenzie, S. (2008). A close look at work and life balance/wellbeing in the Victorian commercial building and construction sector Building Industry Consultative Council, Melbourne.

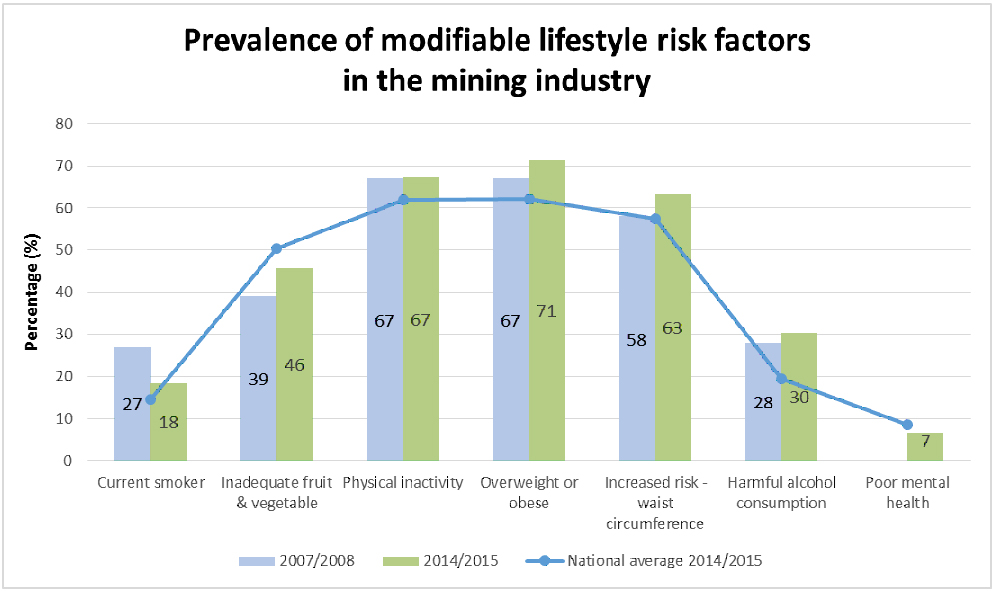

Health status of the mining and resource industry

A diverse range of supply chain organisations service the mining and resource sector and can include: manufacturing, construction, transport and storage, retail, mine camp management services and hospitality services2.

According to the 2014-15 National Health Survey, when compared with all other industries, mining and resource workers have higher rates of smoking, physical inactivity, harmful alcohol consumption, obesity levels, and inadequate fruit and vegetable consumption compared to the national average. Since 2007-08 there have been slight improvements with less workers smoking (see graph below).

Click on graph to view larger version.

National Healthy Survey 2014-15 and 2007-08: Prevalence of modifiable risk factor results for the construction industry.1 Note: Poor mental health was not measured in 2007-08 National Health Survey.

In addition to smoking, poor nutrition, harmful alcohol consumption, physical inactivity, obesity and mental health risk factors, Queensland workers in occupations servicing the mining and resources sector also experience high incidence of1,3:

- fatigue from long working hours and shift work 5,11

- psychological stress 5,11

- depression 5,11

- substance abuse 5,11

- sexually transmissible infections. 5,11

Industry factors that contribute to poor health

- Sedentary occupations can lead to increased risk of injuries, overweight and obesity.

- Over long periods of time, sedentary occupations can contribute to chronic diseases and early mortality. 9-11

- The fly-in fly-out (FIFO) work culture can contribute to harmful alcohol consumption and poor mental health.3,4

- FIFO and drive-in drive-out (DIDO) occupations can increase fatigue, reduce opportunities for recreational activities and social participation with family, friends and the community.3,4Long working hours and shift work can cause a variety of illnesses such as gastrointestinal disease, cardiovascular disease, and poor mental health, which are often associated with weight gain and the risk of being overweight.7 The safety issues of these can lead to reduced alertness affecting safe operation of plant and machinery. 6-8

- Shared and communal accommodation can provide an environment conducive to the transmission of a number of germs that can cause illnesses in people, such as colds and flu, gastroenteritis (stomach complaints), fungal and bacterial skin infections and scabies.12

Impact of worker health and wellbeing on safety and business performance

Workers' health impacts on all parts of the resources sector supply network, including principal contractors, trade sub-contractors, labour hire firms and project clients. The effects of poor health in the resources industry can be seen in things such as injury rates and workers' compensation premiums, deadlines, productivity and skills shortages. For example:

- reduced effectiveness and productivity of workers due to impaired physical and mental functioning, leading to project delays

- increased rate of individual and worksite incidents and injuries, illness and absenteeism, leading to higher workers compensation claims/premiums and skills shortages

- accelerated health decline due to physical nature of the work and work environment e.g. sedentary occupations, shift work and fatigue, culture

- increased staff turnover decreases morale, productivity, and has significant operational and financial impacts9

- smokers have higher risks of injury than non-smokers13

- employees with high body mass index (BMI) have higher absenteeism rates than workers with healthy weight14

- injury risks higher for employees who are overweight and obese13

- employees with unhealthy BMI have higher rates of sickness, disability and workers' compensation events15

- shift work is associated with poor job performance, fatigue, increased weight, and type 2 diabetes.7

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2014/2015 National Healthy Survey: Prevalence of modifiable risk factor results by industry [Internet]. Canberra (AUST): ABS; 2016. [Cited 2 August 2016]. Available from: http://www.abs.gov.au/australianhealthsurvey

- Parliament of Australia. The Australian Resources Sector its contribution to the nation, and a brief review of issues and impacts [Internet]. Canberra (AUST): PA; 2016. [Cited 25 August 2016]. Available from: https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/BN/1011/AustResources

- Kinnear S, Kabir A, Mann J, Bricknell L. The need to measure and manage the cumulative impacts of resource development on public health: an Australian perspective, current topics in public health [Internet]. InTech 2013. [Cited 2 September 2016]. Available from: http://www.intechopen.com/books/howtoreference/current-topics-in-public-health/the-need-to-measure-and-manage-the-cumulative-impacts-of-resource-development-on-public-health-an-au

- Education and Health Standing Committee. The impact of FIFO work practices on mental health – final report 2015. Perth: Parliament of Western Australia; 2015.

- Carlisle KN, Parker AW. Psychological distress and pain reporting in Australian coal miners [Internet]. Safety and Health at Work 2014; 5:203-209. [Cited 2 September 2016]. Available from: http://www.e-shaw.net/article/S2093-7911(14)00053-5/abstract

- Vyas MV, Garg AX, Iansavhicus AV, Costella J, Donner A, Laugsand LE, Janskzy I, Mrkobrada M, Parraga G, Hackam DG. Shiftwork and vascular events: systematic review and meta-analysis [Internet]. British Medical Journal 2012; 345. [Cited 25 August 2016]. Available from: http://www.bmj.com/content/345/bmj.e4800

- Proper KI, van de Langenberg D, Rodenburg W, Vermeulen RCH, van der Beek, AJ, van Steeg H, van Kerkhof LWM. The relationship between shift work and metabolic risk factors: a systematic review of longitudinal studies [Internet]. American Journal of Preventative Medicine 2016; 50(5): e147-e157. [Cited 2 September 2016]. Available from: http://www.ajpmonline.org/article/S0749-3797(15)00760-6/abstract

- Caruso C. Negative impacts of shift work and long work hours. Rehabilitation Nursing 2014; 39(1):16-25.

- Centre for Social Responsibility in Mining. Workforce turnover in FIFO mining operations in Australia: an exploratory study - summary report [Internet]. Brisbane (AUST): Sustainable Minerals Institute, UQ; 2013.

- Straker L, Dunstan D, Gilson N, Healy G. Sedentary work – evidence on an emergent work health and safety issue – final report [Internet]. Canberra (AUST): SWA; 2016. [Cited 23 August 2016]. Available from: https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/resources-and-publications/reports/sedentary-work-evidence-emergent-work-health-and-safety-issue

- Wilmot EG, Edwardson CL, Ahana FA, Davies MJ, Gorely T, Gray LJ, Khunti K, Yates T, Biddle SJH. Sedentary time in adults and the association with diabetes, cardiovascular disease and death: systematic review and meta-analysis [Internet] 2012; 55:2895-2905. [Cited 23 August 2016]. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00125-012-2677-z

- Scholtz J, Nieuwoudt R. Medical services in Moranbah and the impact of non-residential workers, submission to the House of Representatives Standard Committee on Regional Australia, Inquiry into the use of 'fly-in, fly-out' (FIFO) workforce practices in regional Australia [Internet]. Moranbah (AUST): Moranbah Medical; 2011. [Cited 25 August].

- Dong XS, Wang W, Largay JA. Occupational and non-occupational factors associated with work-related injuries among construction workers in the USA [Internet]. International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health 2015; 37(1):142-150. [Cited 23 August 2016]. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/274259766_Occupational_and_non-occupational_factors_associated_with_workrelated_injuries_among_construction_workers_in_the_USA

- Casimirri E, Vaccari A, Schito M, Bonci M, Stendardo M, Stefanati A, Nardini M, Boschetto P. Chronic diseases are strongly associated with sickness absences in a sample of Italian public employees [Internet]. International Journal of Occupational Medicine & Environmental Health 2014; 27(3):343-354. [Cited 23 August 2016]. Available from: http://link.springer.com/article/10.2478/s13382-014-0256-x?no-access=true

- Van Nuys K, Globe D, Ng-Mak D, Cheung H, Sullivan J, Goldman D. The association between obesity and employer costs: evidence from a panel of U.S. employers [Internet]. American Journal of Health Promotion 2014; 28(5)277-285. [Cited 2 September 2016]. Available from: http://www.ajhpcontents.com/doi/full/10.4278/ajhp.120905-QUAN-428

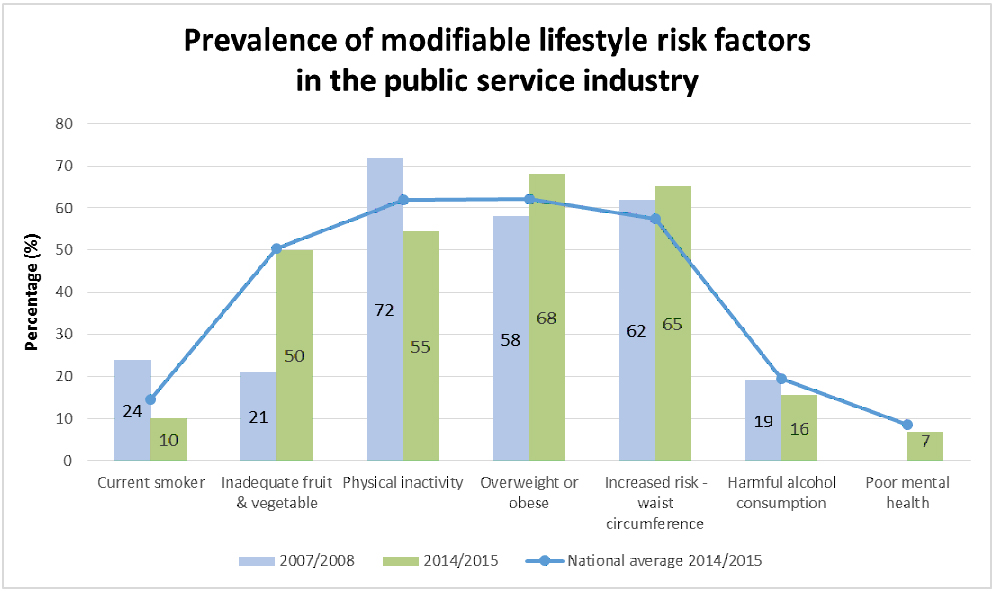

Health status of public service industry

Public service workers are likely to share the same risk factors for chronic disease as the general population with overweight or obesity rates and waist circumference being higher than the national average. Since 2007-08 smoking rates have decreased, physical activity levels have increased and consumption of harmful alcohol levels have decreased (see graph below).

Click on graph to view larger version.

National Healthy Survey 2014-15 and 2007-08: Prevalence of modifiable risk factor results for the construction industry.1 Note: Poor mental health was not measured in 2007-08 National Health Survey.

Industry factors that contribute to poor health

- Ageing workforce

- The average age of a permanent employee in the Queensland Public Service (QPS) is 44.4 years.

- 33.4 per cent are aged 50 years or older, and in age groups where the incidence of illness is higher.

- A large percentage of QPS employees have sedentary jobs. There is emerging evidence suggesting that workplaces with a large proportion of their workforce sedentary due to computer, telephone and other desk/workstation-based work, are at increased risk for chronic diseases such as type 2 diabetes and overweight and obesity. This is irrespective of an individual's level of physical activity.3,4

Impact of worker health and wellbeing on safety and business performance

Sedentary behaviour is associated with cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, higher waist circumference, psychological distress and some cancers.3,4

Unhealthy workers are:

- less productive

- are at increased risk of injury and increased costs to business from absenteeism and presenteeism.5

Overweight and obese workers have higher rates of disability and a greater number of sick days, injury and workers' compensation claims.5

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2014/2015 National Healthy Survey: Prevalence of modifiable risk factor results by industry [Internet]. Canberra (AUST): ABS; 2016. [Cited 2 August 2016]. Available from: http://www.abs.gov.au/australianhealthsurvey

- Public Service Commission. Queensland public sector quarterly workforce profile 2016 [Internet]. Brisbane (AUST): State of Queensland; 2016. [Cited 23 August 2016].

- Straker L, Dunstan D, Gilson N, Healy G. Sedentary work – evidence on an emergent work health and safety issue – final report [Internet]. Canberra (AUST): SWA' 2016. [Cited 23 August 2016]. Available from: https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/resources-and-publications/reports/sedentary-work-evidence-emergent-work-health-and-safety-issue

- Wilmot EG, Edwardson CL, Ahana FA, Davies MJ, Gorely T, Gray LJ, Khunti K, Yates T, Biddle SJH. Sedentary time in adults and the association with diabetes, cardiovascular disease and death: systematic review and meta-analysis [Internet] 2012; 55:2895-2905. [Cited 23 August 2016]. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00125-012-2677-z

- Lehnert T, Sonntag K, Konnopka A, Riedel-Heller S, Konig HH. Economic costs of overweight and obesity [Internet]. Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2013; 27:105-115. [Cited 5 September 2016]. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1521690X1300016X

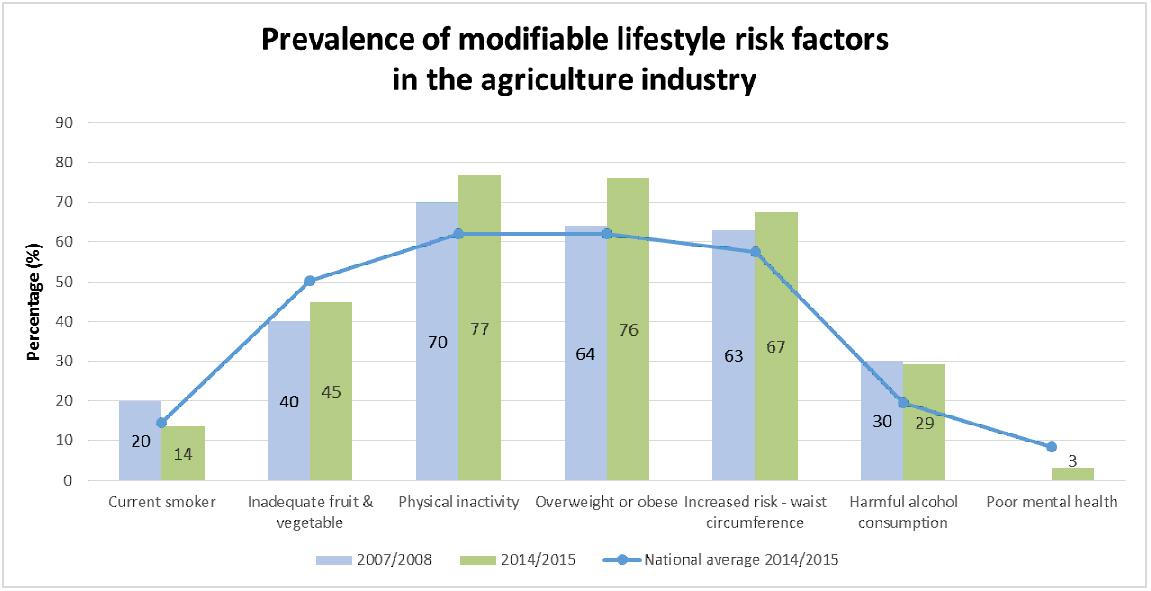

Health status of the agriculture industry

Compared to people living in major cities and inner regional areas, people living in outer regional, rural and remote areas are more likely to engage in high risk behaviours2. Since 2007-08 smoking rates have decreased and consumption of harmful alcohol levels have decreased (see graph below):

Click on graph to view larger version.

National Healthy Survey 2014-15 and 2007-08: Prevalence of modifiable risk factor results for the construction industry.1 Note: Poor mental health was not measured in 2007-08 National Health Survey.

When compared with the average Australian male aged 25 to 74, male farmers and farm managers experience higher death rates from2:

- coronary artery disease and certain cancers

- respiratory diseases, such as chronic asthma and bronchial infections

- stress, depression and other mental health issues.

The 2013 National Drug Strategy Household Survey shows that in the rural sector:

- harmful alcohol consumption and smoking is greater with increasing remoteness

- men, youths and those working in the farming industry are more likely to drink at harmful levels

- alcohol related injuries that result in death and/or hospitalisations are higher for rural residents.

Industry factors that contribute to poor health

- Agricultural workers have physically hazardous occupations.2 Increasing innovation of agricultural practices means that workers are participating in less physical activity.4,5 Environmental factors such as drought, flood and bushfire intensify co-morbidities and psychological distress.4,5

- Agricultural and rural workers often have less access and availability of healthy food and sport and recreational facilities due to remoteness and geographical locations.2

- Queenslanders living in rural and remote areas also have lower access and usage of services than those living in urban settings.2 Harmful alcohol consumption increases with remoteness and isolation.3

- Males living in rural and remote areas are less likely to seek assistance for physical and mental health conditions.3

- Chronic stress and limited social interaction can also increase the risk of psychological distress.4,5

- Living in a rural location often requires more driving than those living in urban settings resulting in a higher number of motor vehicle incidents.2

- 47 per cent of agricultural workers are over 55 years of age where the incidence of chronic disease and musculoskeletal injuries are higher and the time it takes to return to work is often longer.6

Impact of worker health and wellbeing on safety and business performance

- Harmful alcohol consumption may reduce alertness which can lead to increased injuries, incidents and lower productivity in the workplace.5

- Rural Australians have higher rates of chronic disease and mental health issues compared with those living in urban areas, which leads to lower productivity and higher sick leave.1,2,4,5,7

- Work-related stress can cause a variety of health issues including cardiovascular disease, musculoskeletal disorders, gastrointestinal disorders, metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes.8

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2014/2015 National Healthy Survey: Prevalence of modifiable risk factor results by industry [Internet]. Canberra (AUST): ABS; 2016. [Cited 2 August 2016]. Available from: http://www.abs.gov.au/australianhealthsurvey

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. A snapshot of men's health in regional and remote Australia. Rural health series no. 11. Cat. No. PHE 120 [Internet]. Canberra (AUST): AIHW; 2010. [Cited 23 August 2016]. Available from: http://www.aihw.gov.au/publication-detail/?id=6442468343

- AIHW. National Drug Strategy Household Survey detailed report: 2013. Drug statistics series no. 28. Cat. No. PHE 183 [Internet]. Canberra: AIHW; 2014. [Cited 23 August 2016. Available from: http://www.aihw.gov.au/publication-detail/?id=60129549469

- Brumby S, Chandrasekara A, Kremer P, Lewandowski P. Cardiovascular risk factors and pshychological distress in Australian farming communities. Australian Journal of Rural Health 2012; 20:131-137.

- Brumby S, Kennedy A, Chandrasekara A. Alcohol consumption, obesity, and psychological distress in farming communities – an Australian study. The Journal of Rural Health 2013; 29:311-319.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics 2012. 4102.0 Australian Social Trends [Internet]. Canberra (AUST): ABS; 2012. [Cited 23 August 2016]. Available from: http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/allprimarymainfeatures/EED42391CD269634CA257B4800143EAC

- Safe Work Australia. The Australian workplace barometer: report on psychosocial safety climate and worker health in Australia [Internet]. Canberra (AUST): SWA; 2012. [Cited 23 August 2016]. Available from: https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/resources-and-publications/reports/australian-workplace-barometer-report-psychosocial-safety-climate-and-worker-health-australia

- Leka S & Jain A. Health impact of the psychosocial hazards of work: an overview. Geneva (CHE): WHO; 2010.

- Straker L, Dunstan D, Gilson N, Healy G. Sedentary work – evidence on an emergent work health and safety issue – final report [Internet]. Canberra (AUST): SWA' 2016. [Cited 23 August 2016]. Available from: https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/resources-and-publications/reports/sedentary-work-evidence-emergent-work-health-and-safety-issue

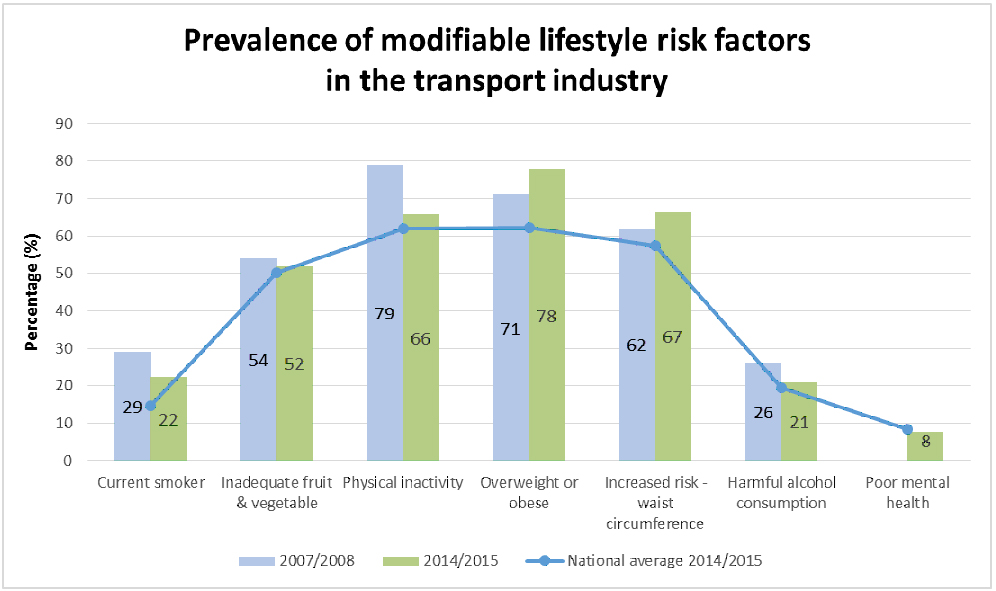

Health status of the transport industry

Results of a survey by the Department of Health and Ageing 1 showed that all modifiable risk factors in the transport industry are above the national average. Since 2007-08 smoking rates have decreased, physical activity levels have increased and consumption of adequate fruit and vegetables have increased (see graph below):

Click on graph to view larger version.

National Healthy Survey 2014-15 and 2007-08: Prevalence of modifiable risk factor results for the construction industry.1 Note: Poor mental health was not measured in 2007-08 National Health Survey.

The industry also has an ageing workforce with 46 per cent of workers over the age of 45. This means almost half of workers are in age groups that have a higher rate of injury and illness than younger workers.6

There is also the increased risk of vehicle incidents from undiagnosed and/or untreated medical conditions such as heart disease and sleep disorders.3

Industry factors that contribute to poor health

- Transport drivers do not have a 'workplace' as such. Their 'workplace' is their vehicle.

- Transport work, especially driving, is largely sedentary, with only brief periods of physical activity (e.g. during loading and unloading).

- Transport drivers often work long and irregular working hours and spend long period's alone.2-5

- 64 per cent of drivers in the transport industry have a performance based wage structure.14 Time pressures and tight deadlines are common.

- Performance based and casual employment places additional pressures on workers, most notably time pressures, and a reluctance to take leave for holidays, sickness or carer duties.14

- In the past there has been a strong industry emphasis on being 'fit for work' rather than a more holistic approach to employee health and wellbeing. There are health standards for driver licensing (such as Jet's Law). There is further work needed to embed effective work health and wellbeing interventions that influence the way work is organised to create a healthy workplace.

Impact of worker health and wellbeing on safety and business performance

The effects of poor health in the transport industry can be seen in things such as injury rates and workers' compensation premiums, and productivity and skills shortages. For example:

- development of sleep apnoea (strongly associated with obesity), which increases the risk of fatigue7

- raised levels of fatigue and reduced alertness, affecting safe operation of plant and vehicles7

- reduced effectiveness and productivity of workers due to impaired physical and mental functioning3

- increased rate of injuries, illness and absenteeism, leading to higher workers compensation claims/premiums and skills shortages3

- sedentary behaviour is associated with cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, higher waist circumference, psychological distress and some cancers8

- long working hours are associated with higher rates of depression, fatigue, type 2 diabetes, musculoskeletal disorders, gastrointestinal disorders, cardiovascular disease and some cancers9

- smokers have higher risks of injury than non-smokers10

- injury risks are higher for employees who are overweight and obese11,12

- employees with an unhealthy BMI have higher rates of sickness, disability and workers' compensation events.11,12

Additionally, the ageing workforce and the increasing rates of chronic disease in the transport and storage industry make retention one of the biggest issues facing businesses. The cost to replace a worker is estimated to be up to 150 per cent of the driver's annual salary.13

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2014/2015 National Healthy Survey: Prevalence of modifiable risk factor results by industry [Internet]. Canberra (AUST): ABS; 2016. [Cited 2 August 2016]. Available from: http://www.abs.gov.au/australianhealthsurvey

- Apostolopoulos Y, Sönmez S, Shattell M, Haldeman L, Strack R, Jones V. - Barriers to truck drivers' healthy eating: Environmental influences and health promotion strategies [Internet]. Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health 2011; 26(2):122–143. [Cited 23 August 2016]. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/15555240.2011.573754

- Apostolopoulos Y, Sönmez S, Shattell MM, Belzer M. Worksite-induced morbidities among truck drivers in the United States [Internet]. AAOHN Journal: Official Journal of the American Association of Occupational Health Nurses 2010; 58(7):285–296. [Cited 23 August 2016]. Available from: http://whs.sagepub.com/content/58/7/285.long

- Ng MK, Yousuf B, Bigelow PL, Van Eerd D. Effectiveness of health promotion programmes for truck drivers: a systematic review [Internet]. Health Education Journal 2015; 74(3):270-286. [Cited 23 August 2016]. Available from: http://hej.sagepub.com/content/74/3/270.full.pdf+html

- Australian Rotary Health Research Fund. Health Survey of the NSW Transport Industry. 2008Safework https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/resources-and-publications/fact-sheets/transport-and-storage-fact-sheet

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Labour Force, Australia, Detailed, Quarterly, Feb 2016, cat. no. 6291.0.55.003. Canberra (AUST): ABS; 2016. Available from: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/6291.0.55.003

- Sharwood LN, Elkington J, Stevenson M, Grunstein RR, Meuleners L, Ivers RQ, Haworth N, Norton R, Wong KK. Assessing sleepiness and sleep disorders in Australian long-distance commercial vehicle drivers: self-report versus an “at home” monitoring device [Internet]. SLEEP 2012; 35(4):469-475. [Cited 18 August 2016]. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/sleep/article/35/4/469/2558854

- Straker L, Dunstan D, Gilson N, Healy G. Sedentary work – evidence on an emergent work health and safety issue – final report [Internet]. Canberra (AUST): SWA' 2016. [Cited 23 August 2016]. Available from: https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/resources-and-publications/reports/sedentary-work-evidence-emergent-work-health-and-safety-issue

- Virtanen M, Heikkila K, Jokela M, Ferrie JE, Batty GD, Vahtera J, Kivimaki M. Long Working Hours and Coronary Heart Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. American Journal of Epidemiology [Internet] 2012; 176(7):586-596. [Cited 19 August 2016]. Available from: http://aje.oxfordjournals.org/content/176/7/586.long

- Lim S et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010 [Internet]. The Lancet 2012; 380: 2224-2260. [Cited 5 September 2016]. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0140673612617668

- Van Nuys K, Globe D, Ng-Mak D, Cheung H, Sullivan J, Goldman D. The association between obesity and employer costs: evidence from a panel of U.S. employers [Internet]. American Journal of Health Promotion 2014; 28(5)277-285. [Cited 2 September 2016]. Available from: http://www.ajhpcontents.com/doi/full/10.4278/ajhp.120905-QUAN-428

- Lehnert T, Sonntag K, Konnopka A, Riedel-Heller S, Konig HH. Economic costs of overweight and obesity [Internet]. Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2013; 27:105-115. [Cited 5 September 2016]. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1521690X1300016X

- Australian Government Comcare. Benefits to business: the evidence for investing in worker health and wellbeing. Canberra (AUST): Comcare; 2014. Available from: http://www.comcare.gov.au/Forms_and_Publications/publications/services/safety_and_prevention/safety_and_prevention/bene_to_busin_the_evid_for_invest_in_work_health_wellbeing

- National Transport Commission and Michael Quinlan. 2008. Safe Payments: Addressing the Underlying Causes of Unsafe Practices in the Road Transport Industry. Melbourne: National Transport Commission.

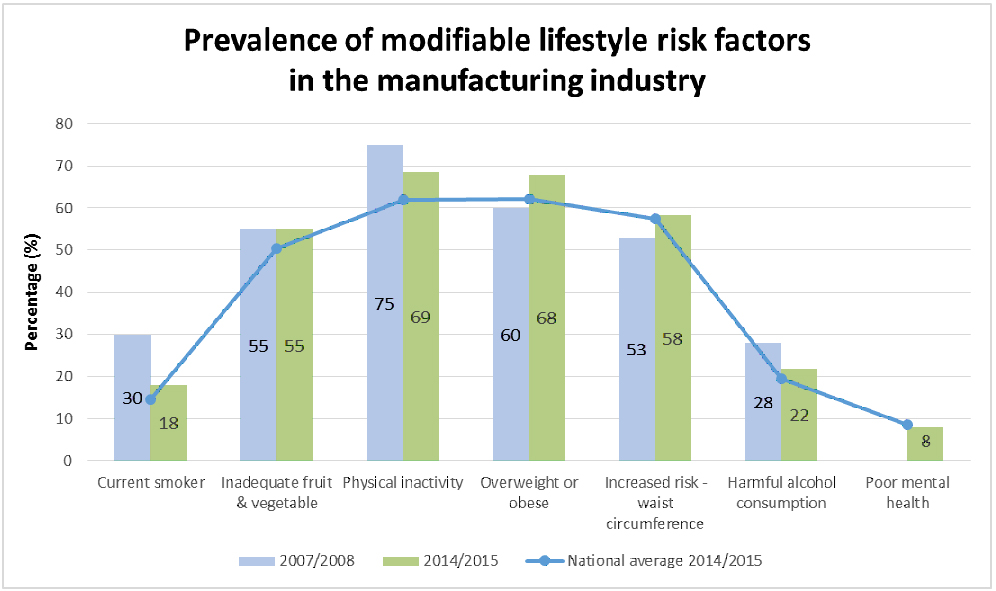

Health status of the manufacturing industry

The manufacturing industry is comprised of a diverse range of sectors including: food and beverage production, clothing and textiles, furniture, wood and paper production, chemical and pharmaceutical production and transport and machinery production.2

Results of a survey by the Department of Health and Ageing1 showed that all modifiable risk factors in the manufacturing industry are above the national average. Since 2007-08 smoking rates have decreased, physical activity levels have increased and consumption of harmful alcohol levels have decreased (see graph below):

Click on graph to view larger version.

National Healthy Survey 2014-15 and 2007-08: Prevalence of modifiable risk factor results for the construction industry.1 Note: Poor mental health was not measured in 2007-08 National Health Survey.

Workers in the manufacturing industry are also exposed to airborne particulates, noise, chemicals and vibration hazards.3 45 per cent of all claims are a result of musculoskeletal injuries.4

Industry factors that contribute to poor health

- Shift work, irregular hours, sedentary nature of work and difficulty accessing healthy food are all factors shown to contribute to poor worker health.3

- Manufacturing workers are often required to work long work hours and increased workloads over holiday periods.3 Many manufacturing jobs require employees to work quickly, with undivided attention or without regular breaks.3

- Manufacturing workers are regularly exposed to dangerous machinery and equipment, repetitive movements, heavy lifting and hazardous chemicals which can cause injury and disease.3

- The manufacturing industry is an ageing workforce and 73 per cent of manufacturing workers are male.5 Older workers have higher rate of injury and illness and males are less likely to seek medical assistance.

- Many workers in the manufacturing industry have a performance based wage structure and casual employment causes a reluctance to take leave for sickness or holidays.3

Impact of worker health and wellbeing on safety and business performance

- High job demands increases the risk of safety shortcuts and fatigue which can lead to incidents or injury.3,6

- Long working hours and shift work is associated with poorer health outcomes including depression, fatigue, type 2 diabetes, musculoskeletal disorders, gastrointestinal disorders, cardiovascular disease and some cancers.7 Those with co-morbidities are at an increasingly higher risk.7

- Chronic disease, type 2 diabetes and depression have been found to increase the risk of workplace injury in the manufacturing industry.6

- Fatigue is associated with poor diet, inadequate physical activity and increased alcohol consumption.8

- Impaired physical and mental functioning lowers worker safety and productivity increasing presenteeism. Evidence has shown workers that averaged three to four hours of overtime a day were around 1.8 times more likely to develop certain chronic diseases.9 Increased absenteeism due to injury and illness leads to lost productivity time and skilled worker shortages.

- Sedentary behaviour is associated with cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, higher waist circumference, psychological distress and some cancers.10

- Safe Work Australia. Work health and safety perceptions: Manufacturing industry [Internet]. Canberra (AUST): SWA; 2015. [Cited 16 August 2016] - Available from: http://www.healthandsafetyhandbook.com.au/report-health-and-safety-perceptions-in-the-manufacturing-industry/

- WorkSafe Queensland. Manufacturing industry –about manufacturing [Internet]. Brisbane (AUST): WSA; 2016. [Cited 16 August 2016]. Available from: https://www.worksafe.qld.gov.au/manufacturing

- SafeWork Australia. Statistics on work-related musculoskeletal disorders [Internet]. Canberra (AUST): SWA;2016. Available from: https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/resources-and-publications/statistical-reports/statistics-work-related-musculoskeletal-disorders

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Labour Force, Australia, Detailed, Quarterly, Feb 2016. Cat. No. 6291.0.55.003. [Internet]. Canberra: ABS; 2016. [Cited 16 August 2016]. Available from: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/6291.0.55.003

- Kubo J, Goldstein BA, Cantley LF, Tessier-Sherman B, Galusha D, Slade MD, Chu IM, Cullen MR. Contribution of health status and prevalent chronic disease to individual risk for workplace injury in the manufacturing environment. Occupational and Environmental Medicine [Internet] 2014; 71:159:166. [Cited 16 August 2016]. Available from: http://oem.bmj.com/content/early/2013/10/16/oemed-2013-101653.full

- Caruso C. Negative impacts of shift work and long work hours. Rehabilitation Nursing 2014; 39(1):16-25.

- Dorrian J, Skinner N, Pisaniello. Work quality, not just quantity: work related predictors of psychological distress, work-family interaction and alcohol consumption [Internet]. Adelaide (AUST): Adelaide Centre for Work and Life; 2010. [Cited 16 August 2016]. Available from: http://www.unisa.edu.au/hawkeinstitute/cwl/default.asp

- Virtanen M, Heikkila K, Jokela M, Ferrie JE, Batty GD, Vahtera J, Kivimaki M. Long Working Hours and Coronary Heart Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. American Journal of Epidemiology [Internet] 2012; 176(7):586-596. [Cited 19 August 2016]. Available from: http://aje.oxfordjournals.org/content/176/7/586.long

- Straker L, Dunstan D, Gilson N, Healy G. Sedentary work – evidence on an emergent work health and safety issue – final report [Internet]. Canberra (AUST): SWA' 2016. [Cited 23 August 2016]. Available from: https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/resources-and-publications/reports/sedentary-work-evidence-emergent-work-health-and-safety-issue

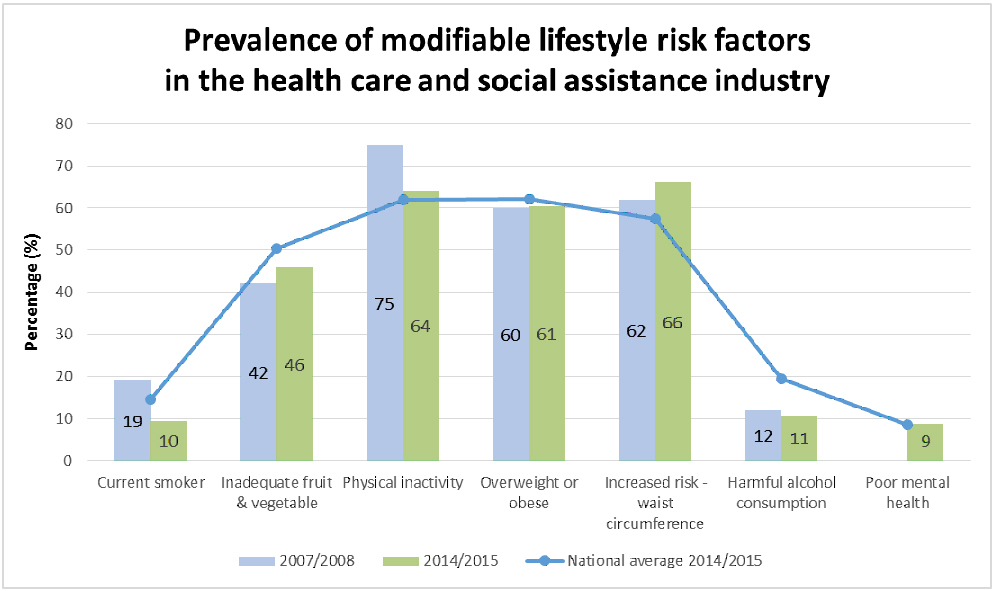

Health status of the health care and social assistance industry

The health care and social assistance industry includes hospital and medical services, mental health and allied health, aged and residential care, as well as child care and social assistance services.1

Comparison of health care and social assistance workers' health with the wider Australian adult population show the industry to have higher than national averages for physical inactivity and waist circumference. Since 2007-08 smoking rates have decreased, physical activity levels have increased and consumption of harmful alcohol levels have decreased (see graph below):

Click on graph to view larger version.

National Healthy Survey 2014-15 and 2007-08: Prevalence of modifiable risk factor results for the construction industry.1 Note: Poor mental health was not measured in 2007-08 National Health Survey.

Health care and social assistance workers also experience high rates of musculoskeletal injury, sleep disorders, and psychological distress.2-4

Industry factors that contribute to poor health

- Employment in health care and social assistance has grown 64 per cent in the last ten years.5 Health care and social assistance is the largest industry sector in Queensland, accounting for 12 per cent of Queensland's workforce.5 This sector accounts for 15 per cent of workers compensation claims in Queensland and has more serious injury claims than any other industry.5 Workforce shortages and time off work due to illness or injury can impact on employee and patient safety as a result of overworked or underqualified staff.4,7

- A large percentage of health care and social assistance jobs involve long working hours and shift work which is associated with poorer health outcomes including depression, fatigue, type 2 diabetes, musculoskeletal disorders, gastrointestinal disorders, cardiovascular disease and some cancers.6 Changes to client needs, service delivery, qualifications and workforce shortages have resulted in longer work hours and heavier workloads.4,7

- 45 per cent of health care and social assistance workers are over 45 years of age2 where the incidence of chronic disease and musculoskeletal injuries are higher and the time it takes to return to work is often longer. 63 percent of claims from health and community care workers aged between 50 and 59 years are due to musculoskeletal injuries and diseases.3

- Health care and social assistance workers are more likely to experience bullying, emotional abuse and aggressive or violent events which can cause psychological distress.7 Recent studies have identified harmful alcohol consumption as an emerging issue for nurses as a result of psychological distress.4

Impact of worker health and wellbeing on safety and business performance

Shift work and long working hours have been shown to adversely affect physical and mental health, job performance and workplace productivity.6 Work-related stress can cause a variety of health issues including cardiovascular disease, musculoskeletal disorders, gastrointestinal disorders, metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes.8 Fatigue can result in poor diet, inadequate physical activity and increased harmful alcohol consumption.9 Reduced alertness due to fatigue can lead to increased injuries and accidents in the workplace.10

- Australian Health Directory. Health industry resources – Associations [Internet]. Melbourne (AUST): AHD; 2016. [Cited 23 August 2016]. Available from: http://www.healthdirectory.com.au/Health_industry_resources/Associations/search

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2014/2015 National Healthy Survey: Prevalence of modifiable risk factor results by industry [Internet]. Canberra (AUST): ABS; 2016. [Cited 2 August 2016]. Available from: http://www.abs.gov.au/australianhealthsurvey

- WorkSafe Queensland. Musculoskeletal injury prevention and suitable duties are crucial for ageing workforce [Internet]. Brisbane (AUST): WSQ; 2016. [Cited 23 August 2016]. Available from: https://www.worksafe.qld.gov.au/health/articles/musculoskeletal-injury-prevention-and-suitable-duties-are-crucial-for-ageing-workforce

- Perry L, Lamont S, Gallagher R, Duffield C. The mental health of nurses in acute teaching hospital settings: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Nursing 2015; 14:15. Available from: http://bmcnurs.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12912-015-0068-8

- Industry Sector Standing Committees. Health care and social assistance statistic summary. Brisbane (AUST): OIR; 2016. [Cited 23 August 2016].

- Caruso C. Negative impacts of shift work and long work hours. Rehabilitation Nursing 2014; 39(1):16-25.

- NSW Nurses and Midwives Association. Work health and safety essentials for nurses and midwives. WorkCover NSW; 2013.

- Leka S & Jain A. Health impact of the psychosocial hazards of work: an overview. Geneva (CHE): WHO; 2010.

- Dorrian J, Skinner N, Pisaniello. Work quality, not just quantity: work related predictors of psychological distress, work-family interaction and alcohol consumption. Adelaide (AUST): Adelaide Centre for Work and Life; 2010.

- Arlinghaus A, Lombard DA, Willetts JL, Folkard S, Christiani D. A structural equation of modelling approach to fatigue-related risk factors for occupational injury. American Journal of Epidemiology 2012; 176(7):597-607.

Health status of small business

Small businesses are made up of fewer than 20 employees.2 Small businesses account for almost half (43 per cent) of the Queensland workforce. There are around 406,000 small businesses in Queensland which represent 96 per cent of businesses state wide.3 Small business owners and workers are likely to have similar risk factors for chronic disease as the general population of Australia.1

- Overweight or obese (62.1 per cent)

- Physically inactive (61.96 per cent)

- Low vegetable and fruit intake (50.3 per cent)

- Current smoker (14.6 per cent)

- Harmful alcohol consumption (19.5 per cent).

Industry factors that contribute to poor health

Organisational structure

Small businesses are often owner operator companies where there are a small number of staff who carry out multiple roles and are emotionally and financially invested.4 This can lead to role ambiguity, work/life imbalance and financial concerns which lead to stress, fatigue and depression.4

A smaller number of staff may mean small businesses have less resources and less likely to prioritise health, safety and wellbeing practices compared with larger businesses.4,5

Small businesses may have limited financial resources to make changes regarding health and safety.4,5 As a result, this can lead to a higher number of industrial incidents and poorer working conditions than large organisations.4,5

Long working hours

Small business owners and workers often have long working hours which is associated with poorer health outcomes.

Working long hours is associated with higher rates of depression, fatigue, type 2 diabetes, musculoskeletal disorders, gastrointestinal disorders, cardiovascular disease and some cancers.7,8

Impact of worker health and wellbeing on safety and business performance

Evidence has shown that owner/managers lose significant productivity time due to absenteeism and presenteeism due to psychological distress.4 Work-related stress can cause a variety of health issues including cardiovascular disease, musculoskeletal disorders, gastrointestinal disorders, metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes.6 This can have a greater financial impact on a small workplace.4

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. The Australian Health Survey 2014-2015 – first results. Health risk factors by industry [Internet]. Canberra (AUST): ABS; 2016. [Cited 23 August 2016]. Available from: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/4364.0.55.001~2014-15~Main%20Features~Key%20findings~1

- Australian Securities and Investments Commission. Small business – what is small business [Internet]. Canberra (AUST): ASIC; 2015. [Cited 23 August 2016]. Available from: http://www.asic.gov.au/for-business/your-business/small-business/small-business-overview/small-business-what-is-small-business/

- Queensland Government. Advancing Small Business Queensland [Internet]. Brisbane (AUST): The State of Queensland; 2016. [Cited 24 November 2016]. Available from: https://www.dtesb.qld.gov.au/small-business/advancing-small-business-queensland

- Cocker F, Martin A, Scott J, Venn A, Sanderson K. Psychological distress, related work attendance and productivity loss in small-to-medium sized enterprise owner/managers [Internet]. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2013; 10:5062-5082.

- Park J, Jeong H, Hong S, Park J, Kim D, Kim J, Kim H. Effects of health and safety and problem recognition on small business facility investment [Internet]. Annals of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 2013; 25:26-36. [Cited 23 August 2016]. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259958693_Effects_of_health_and_safety_problem_recognition_on_small_business_facility_investment

- Leka S & Jain A. Health impact of the psychosocial hazards of work: an overview. Geneva (CHE): WHO; 2010.

- Caruso C. Negative impacts of shift work and long work hours [Internet]. Rehabilitation Nursing 2014; 39(1):16-25. [Cited 2 September 2016]. Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/rnj.107/epdf

- Virtanen M, Heikkila K, Jokela M, Ferrie JE, Batty GD, Vahtera J, Kivimaki M. Long Working Hours and Coronary Heart Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. American Journal of Epidemiology [Internet] 2012; 176(7):586-596. [Cited 19 August 2016]. Available from: http://aje.oxfordjournals.org/content/176/7/586.long

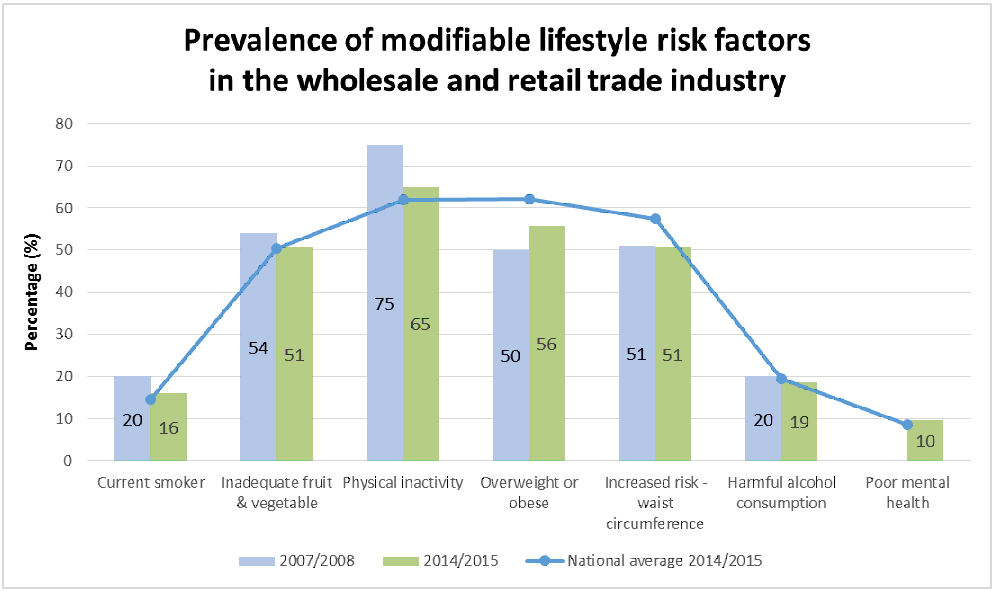

Health status of the wholesale and retail industry

According to the 2014-15 National Health Survey, when compared with all other industries, retail workers have higher rates of smoking, physical inactivity levels, and inadequate fruit and vegetable consumption compared to the national average.

Since 2007-08 there have been slight improvements with less retail workers smoking, more being physically active, eating more adequate fruits and vegetables and less harmful alcohol levels consumed (see graph below).

Click on graph to view larger version.

National Healthy Survey 2014-15 and 2007-08: Prevalence of modifiable risk factor results for the construction industry.1 Note: Poor mental health was not measured in 2007-08 National Health Survey.

The Retail trade industry generally refers to those engaged in the purchase and/or on selling of goods to the public.

Some things to consider when thinking about supporting and promoting the wellbeing activities in this industry include:

- The retail industry is a significant employer of young people. Workers aged 15-24 years account for 40 per cent of workers in retail. These workers are also least likely to apply for workers' compensation.5

- Employment in retail also represents older workers who are phasing out of the workforce or re-entering it after retirement.1

- Nearly half of all workers in retail industry work part time.5

- Sprains and strains account for one third of all injuries.5

Industry factors that contribute to poor health

Long working hours, irregular schedules and shift work

Retail occupations often involve long working hours, irregular schedules and shift work which is associated with poorer health outcomes including depression, fatigue, type 2 diabetes, musculoskeletal disorders, gastrointestinal disorders, cardiovascular disease and some cancers.3,6 Many retail jobs require individuals to take short breaks with little autonomy over work schedules and poorer work-life balances. 6,7,10

High stress environment

Retail workers are more likely to experience emotional abuse and aggression from customers which can cause psychological distress.3

Physical workload

Retail workers are regularly exposed to high physical workloads and demands, repetitive movements, and lifting which can cause injury and disease.3,6

Casual employment

Many workers in the retail industry have casual employment, are involved in temporary work and offered lower wages which cause a reluctance to take leave for sickness or holidays.3

Impact of worker health and wellbeing on safety and business performance

Irregular work schedules, shift work and long working hours, low wage employment and high stress environment can contribute to:

- Obesogenic behaviours, particularly due to the difficulty of eating healthy with short, interrupted breaks and the ability to maintain a healthy diet and exercise regime.6,7 Workers who are overweight and obese have a higher risk of injury and take twice as long off work due to injury.8

- Feelings of tiredness, stress, fatigue or depression which can lead to manifestation of injury and incidents, cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. 9,10

- Poor work life balance leading to health impairments, sleep disorders, alcohol use, depression and anxiety.10 Impaired physical and mental functions lowers worker safety and productivity, increasing presenteeism.9

- Smoking behaviours, which pose higher risk of injury than non-smokers.4

- Anderson, V.P., et al. Occupational fatalities, injuries, illnesses, and related economic loss in the wholesale and retail trade sector - Am J of Ind Med 2010; 52: 673-685

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2014/2015 National Healthy Survey: Prevalence of modifiable risk factor results by industry [Internet]. Canberra (AUST): ABS; 2016. [Cited 2 August 2016]. Available from: http://www.abs.gov.au/australianhealthsurvey

- Carmichael, F. et al. Workplace health and wellbeing in construction and retail: Sector Specific issues and barriers to resolving them. Int J of Workplace Health Management 2016; 9;2: 1-18

- Dong, Z.S., Wantg, Z. & Largay, I.A. (2015)

- Safe Work Australia (2009). - Work-related injuries in Australia, 2005-2016: Retail Industry.

- Strickland, JR et al. Enhancing workplace wellness efforts to reduce obesity: a qualitative study of low-wage workers in St Louis, Missouri, 2013-2014. - Prev Chronic Dis 2015; May 7; 12:E67.

- Strickland, JR et al. Worksite influences on obesogenic behaviours in low-wage workers in St Louis, Missouri, 2013-2014. Prev Chronic Dis 2015; May 7; 12:E66.

- Van Nuys, K., Globe, D., Ng-Mak, D., Cheung, H., Sullivan J & Goldman, D. (2014)

- Virtanen M, Heikkila K, Jokela M, Ferrie JE, Batty GD, Vahtera J, Kivimaki M. Long Working Hours and Coronary Heart Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. American Journal of Epidemiology [Internet] 2012; 176(7):586-596. [Cited 19 August 2016]. Available from: http://aje.oxfordjournals.org/content/176/7/586.long

- Wirtz, A., Narchreiner, D., & Rolfes, K. Working on Sundays-Effects on Safety, Health and Work-Life Balance. Chronobiology International 2017; 28:4: 361-370