Construction dust: respirable crystalline silica

Inhaling respirable crystalline silica (RCS) can lead to serious lung conditions such as silicosis.

Find out more about the risks of dust containing respirable crystalline silica (RCS) and the steps you must take to keep yourself and your workers safe.

Crystalline silica (silicon dioxide) is a common mineral found in many building materials, such as:

- bricks, blocks, pavers, tiles and mortar

- concrete and cement-based products, such as fibre-cement sheeting and autoclaved-aerated concrete

- most rocks, sands, and clays.

When these materials are processed (e.g. cut, sawn, ground, drilled, polished, scabbled or crushed), dust containing RCS can be released.

Other tasks like dry sweeping or using compressed air blowers on dust containing RCS can make it airborne.

The Managing respirable crystalline silica dust exposure in construction and manufacturing of construction elements Code of Practice 2022 (PDF, 1.71 MB) sets out:

- enforceable standards that must be met to minimise the risk of worker exposure to RCS dust in construction work and the manufacturing of construction elements

- information about the risks and impacts of exposure to RCS dust in construction work and the manufacturing of construction elements.

From 1 May 2023, this code of practice will apply if you are working in the construction industry, or a manufacturing business that produces construction materials.

Read the following silica task sheets:

- Stationary masonry saws

- Handheld power saws

- Handheld power saws for cutting fibre-cement board with a blade diameter of 200mm or less

- Walk behind saws

- Drivable saws

- Core saws or drills (rig mounted and handheld)

- Hand and stand mounted drills

- Dowel drilling rigs for concrete

- Vehicle mounted drill rigs for rock and concrete

- Jackhammers and handheld clipping tools

- Handheld grinders for mortar removal

- Handheld grinders for tasks other than mortar removal

- Walk behind milling machines and floor grinders

- Small drivable milling machines (less than half lane)

- Large drivable milling machines (half lane and larger)

- Crushing machines

- Heavy equipment and utility vehicles for grading and excavating tasks

- Heavy equipment and utility vehicles for demo activities

- Dry sweeping

- Compressed air and blowers.

Health effects

RCS particles stay airborne long after other dust particles have settled to the ground and are so small they cannot be seen under normal light. The small particle size means they are easily inhaled deep into the lungs.

RCS is a hazardous chemical and a carcinogen. Inhaling RCS can lead to silicosis, an incurable lung disease that can lead to disability and death. RCS can also contribute to lung cancer, renal cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Silicosis usually follows exposure to RCS over many years, but extremely high short-terms exposures can cause it to develop rapidly.

The video below has been produced by the UK Health and Safety Executive (HSE), and details the first-hand experience of former stone worker, Terry, a sufferer of silicosis. His story shows the importance of:

- recognising that exposure to RCS will damage your body

- knowing the regulatory requirements for working with RCS

- using the best controls available to prevent or reduce exposure

- protecting your own life, as well as those around you.

Silicosis can develop or continue to progress even after exposure to RCS has stopped.

In this film Dr David Fishwick interviews Terry who suffers from silicosis after being exposed to respirable crystalline silica (RCS) at work. Terry worked for over 30 years with different types of stone. He has worked with marble and in recent years with sandstone containing 90% crystalline silica. He has developed silicosis – a serious respiratory condition that will almost certainly shorten his life after breathing in RCS. Silicosis can develop in workers exposed to RCS in a number of industries including construction, stone working, quarrying, brick making and ceramics.

[First imagine appears on the left of screen with footage of a man using a grinder on stone]

[Second imagine appears in the middle of the screen showing a skeleton with silicosis on the lungs]

[Third imagine appears on the right of the screen showing a man blowing into tube]

[Image changes and text appears on the screen "Terry: Former stone worker suffering from silicosis")

[Image changes to show Terry sitting down being interview by Dr David Fishwick]

Terry: The young people are invincible. They're Johnny Concrete's they're unbelievably strong but eventually concrete erodes and so does your body and if you don't look after it, it'll come back. You must protect yourself and be aware of the regulations. You're protecting your own life and other people around you. People say well you know you look healthy don't judge the book by its cover.

[Screen turns black and text appears on screen: Early Life]

David: Just talk me through your early years. You left school when you were a young lad of 16, you started work with marble as a stonemason. Tell me about your health, what were you like?

Terry: Well I started doing karate when I was 13 at school, so you've got all your school curriculum: games, rugby, football, cross-country. Then I started work carried on with my karate became a black belt in karate went on for years actually till in my thirties, training. There was never any problem with my breathing or fitness or anything else you know I used to do a lot of walking fast walking as well. There was never any problem. So I was picking lumps of stone up or chunks of marble so what developed was a very strong upper body and with my karate training my legs as well, plus all the walking I did. So it was like weight training of a day and then I would be doing my karate of a night so I was as fit as a butcher's dog as they say.

[Screen turns black and text appears on screen: Risks from exposure]

David: Can I just ask you an unrelated question because we're talking about it now when you were having a working life working with stone dust has anyone ever told you about the dangers of working with stone dust?

Terry: They'd said that dust isn't good for you but they never ever said about the respiratory silica crystal. Apparently that's the devil among all this nobody ever told me I was never instructed about respiratory silica crystal. As I said to you an old fella had said to me what you breathe in some of it stays in. But you think, you blow your nose and I'm not being crude but when you cough you bring this stuff up and you see brown or red strands of this in your mucus. So you think it's coming out but you don't realise that some of it's staying in and staying there.

[Screen turns black and text appears on screen: Impact on health]

David: Terry when did you first notice that you had problems with your health and particularly your breathing?

Terry: We were in Spain and it was quite warm and it was quite hilly now walking in hills never bothered me before. But we'd been the shops bringing back our groceries and I had to sit down on the pavement because I just couldn't breathe and my wife said what's to do with you I said I can't breathe I've got pains in my chest I'm really breathless. So we sat there for a bit and we took the groceries up in stages and I said there's something wrong and I had a pain in my chest for at least 2 weeks after I came back from Spain and that's why I went to my GP and she sent me then to the hospital to see a lung consultant.

David: And at any time when you were becoming unwell in those few weeks did you ever link it with your workplace and the dust that you'd been exposed to?

Terry: What I thought was I'm getting older so obviously you're not as fit as what you think you are and it's just wear and tear on your body. You know I'm getting older so I've got my shopping and I'm going up a hill. I never realised that my lungs had been damaged and it was now starting to take effect on my general health.

[Screen turns black and text appears on screen: First diagnosed with silicosis]

David: Terry, how did you feel when you were first diagnosed with silicosis?

Terry: I was absolutely devastated because you hear about people with silicosis they're dying. It's like your lungs turn to stone and everything else and as I say I was only a young fella. It was catastrophic really I can't tell you anything else I was crestfallen at the situation through no fault of my own I'd got this disease and how bad is it how fast is going to progress how much longer have I got to live I'm only a young fella. As far as I'm concerned healthy and where do we go from here you know, what is the future holding for me It's like a big black cloud on me all the time.

[Screen turns black and text appears on screen: Effects on his life]

David: So Terry it must have been a very difficult time of your life when you were given this diagnosis of silicosis. How did it affect you both personally and your health?

Terry: I was crestfallen when I got the information I presumed I was fit and always looked after myself and then I'm given this bombshell as I believed a terminal lung disease. Where does that leave me what's going to happen to my wife and family? You know what can I do to minimise the effect of what's happening to me? The situation is I've always been an active person my wife's an active person and so are my children. The situation that was I was like set on the side of any activity because I can't walk fast I can't run definitely can't run I used to do some swimming. When I was swimming eventually I started to get short of breath and if you're in the middle of the swimming pool there's nowhere else to go. So it was too dangerous as far as I was concerned and too painful to push myself get to the side got out got dressed and went home and I've never done it since I try and do as much as I possibly can to minimise this disease. People say well you look healthy don't judge the book by its cover. It's what's inside it's not it's not right and I feel like it all the time I have like a short of breath if you've run a marathon you get like a burn that's what from time to time I feel like if I've walked a little bit further than I should do It's very uncomfortable.

David: If you were walking down the beach or knocking a football around in the park would you still get breathless doing that now?

Terry: You can kick the ball but if I have to go and get the ball I'll walk I can't run I don't run anywhere. That's the end of it I don't run anywhere as I say I used to be a very fit man karate all my life a lot of running a lot of physical exercise press ups sit ups star jumps they're out the question it's not worth doing it because it's so uncomfortable.

[Screen turns black and text appears on screen: Workplace exposure]

David: Terry it's clear to me that from your description you've been exposed to significant amounts of stone dust particularly in the last few years of your working life. What factors do you think contributed to that very heavy exposure?

Terry: Well it was the pressure of work. Pressure of work more than anything else. We were supplying an awful lot of men with an awful lot of material but there was only 3 of us so it was intense very intense it was a smaller area that we worked in the condensity of the amount of work we were doing and the small facility that we worked in. It was just a three tier cake of disaster if you ask me.

[Screen turns black and text appears on screen: Lessons learned]

David: What advice would you give younger people now in your trade about how to do things today to prevent them getting the ill health problems that you have?

Terry: All I can say to all the apprentices who are working with silica you must protect yourself and be aware of the regulations. You're not being a trouble causer you're not a whistle blower you're protecting your own life and other people around you. You must adhere to the regulations and your employers must adhere to the regulations and try and get the best equipment that they can afford.

What the young people are, are invincible. They're Johnny Concrete's they're unbelievably strong and all that carry on but eventually concrete erodes and so does your body and if you don't look after it, it'll come back and it'll do more damage and it'll ruin your lives by not doing what you're supposed to do.

[Imagine changes to show the HSW Logo]

[Text appears on screen: Not for broadcast use – Crown Copyright 2015)

RUN TIME: 8 min 55 sec

Workplace exposure standard

The workplace exposure standard (WES) for RCS is 0.05 mg/m3 over an eight-hour time-weighted average. Guidance on interpreting exposure standards is available in the Guidance on the Interpretation of Workplace Exposure Standards for Airborne Contaminants.

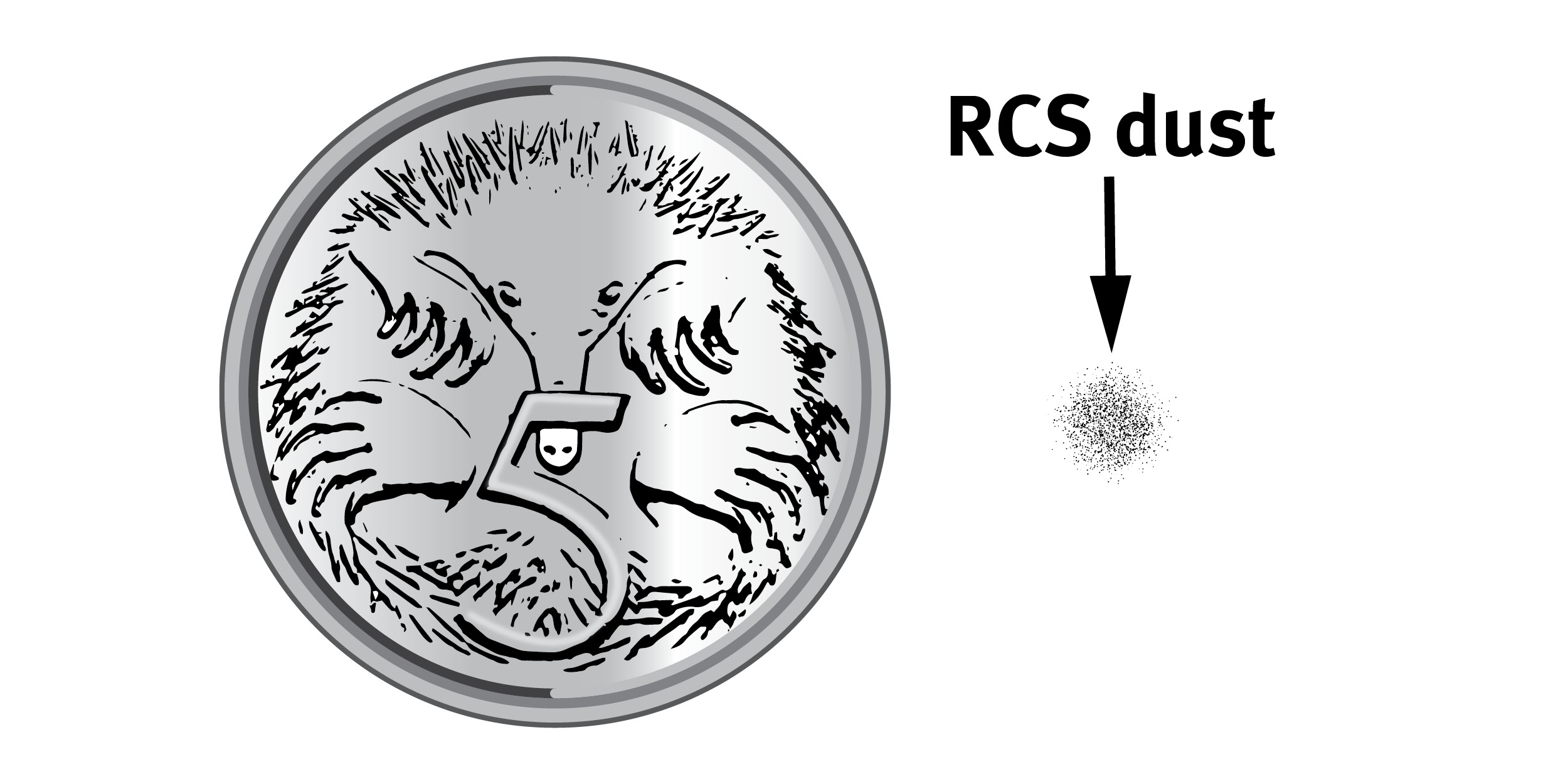

The WES for RCS will be exceeded if the dust you breathe in over a full shift contains more RCS than the amount shown here next to the five cent piece. Reference: HSE

Managing exposure

Identification

You need to identify tasks that use or generate RCS. For each task you should find out if it involves:

- working with materials that contain one per cent or more crystalline silica; and

- generating dust likely to contain RCS; or

- disturbing dust that contains RCS so that it gets into the air.

For example, pre-blended bagged concrete and fibre cement sheeting will contain silica and during use airborne RCS may be generated. Some products will have a label warning of silica content.

Control the risks

You must ensure no-one at the workplace is exposed to RCS at a level above the workplace exposure standard.

Eliminating exposure to RCS is the most effective control measure for managing the risk of work related illness. If exposure cannot be eliminated, it must be minimised so far as is reasonably practicable. This includes short term or one-off tasks.

Reducing the airborne concentration of RCS is more effective than relying on respiratory protective equipment. Look carefully at the control measures that can be used—some are more cost effective and practical for each situation than others.

The Managing respirable crystalline silica dust exposure in construction and manufacturing of construction elements Code of Practice 2022 (PDF, 1.71 MB) sets out effective controls for a range of common construction and manufacturing tasks.

If workers use the controls recommended in the controls table for that task, and ensure they use them correctly, you can be certain that the risk of RCS exposure is being managed effectively.

You can control RCS risks by:

Eliminating or minimising RCS work processes onsite are best achieved in the planning and design stages, in consultation with clients, designers, suppliers and workers.

Examples of eliminating or minimising the risk of RCS include:

- ordering the right size of building materials so less cutting or preparation is needed

- using products with less than one per cent crystalline silica content

- using fibre-cement sheet sheers instead of circular saws

- housekeeping - dry sweeping dust and debris can generate high levels of airborne RCS and other respirable dust. Safer cleaning methods should be used, such as:

- wet sweeping

- using low-pressure water (e.g., hosing down/wiping/mopping of surfaces)

- vacuuming up dust and debris containing silica using an M or H-class vacuum cleaner

- waste disposal - you can reduce dust associated with waste by:

- bagging waste materials before putting them into the bin or skip

- locating bins and skips outdoors where possible

- using water misting systems to keep waste materials damp where possible.

Only use industrial vacuum cleaners and filters that comply with the M or H class requirements of AS/NZS 60335.2.69:2017 Household and similar electrical appliances - Safety - Particular requirements for wet and dry vacuum cleaners, including power brush, for industrial and commercial use (IEC 60335.2.69 ED 5, MOD).

If eliminating or substituting RCS materials or work processes is not practical, you must prioritise other higher order controls:

- isolating the hazard (e.g., enclosing the equipment that generates RCS, or establishing an exclusion zone)

- using engineering controls (e.g., local exhaust ventilation, water suppression).

Common higher order control options include:

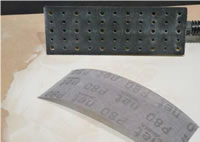

- On-tool extraction

This method removes dust as it is being produced. It is a type of local exhaust ventilation (LEV) system that fits directly onto the tool. This system consists of several individual parts – the tool, capturing hood, an M or H class dust extraction unit or vacuum and tubing.

Examples of on tool extraction (photos courtesy of HSE)

- Water suppression

Water or fine mist suppression can also be used to control RCS dust when LEV is not suitable. However, it needs to be used correctly. This means enough water supplied at the right levels for the whole time that the work is being done. Just wetting the material beforehand does not work.

Examples for use include wet cutting methods for brick, tile, stone and concrete.

Cut-off saw with water suppression (photo courtesy of Stihl)

- Isolation

Fully enclosed operator cabins, such as those found on earthmoving plant have been shown to effectively control exposure to RCS when fitted with properly designed and maintained HEPA air filtration.

Locate RCS work processes outdoors away from other workers where possible.

Indoors separate the RCS work process from other work areas with physical barriers.

RPE does not prevent or control RCS from becoming airborne. It should not be used as the primary means of control, but rather in combination with higher order controls like LEV or water suppression.

No respirator is capable of preventing all airborne RCS from being breathed in.

It is important to choose the right respirator for the job. The fit of a respirator to a worker's face is critical (PDF, 0.86 MB). Have workers fit-tested to ensure the respirator is comfortable and capable of giving the right level of protection. The amount of time the respirator is worn also needs to be considered.

Further information on choosing the right RPE, and fit-testing to make sure it is suitable for the worker, can be found in Managing respirable crystalline silica dust exposure in construction and manufacturing of construction elements Code of Practice 2022 (PDF, 1.71 MB).

You may already have the right controls in place, but are they all working properly?

- When were controls last checked?

- Are they always used when needed?

- Is the RCS exposure controlled?

Controls must be reviewed at least once every five years or earlier in certain situations.

Further information on reviewing controls for RCS can be found in the Managing respirable crystalline silica dust exposure in construction and manufacturing of construction elements Code of Practice 2022 (PDF, 1.71 MB).

Air monitoring

Air monitoring involves testing the breathing zone of the worker to find out how much of a harmful substance is in the air. It determines if a workplace exposure standard has been exceeded and there is a risk to health.

Air monitoring must be carried out to check for airborne RCS at the workplace if:

- you are not certain, on reasonable grounds, if the workplace exposure standard has been exceeded

- you need to work out if there is a risk to health.

The Managing respirable crystalline silica dust exposure in construction and manufacturing of construction elements Code of Practice 2022 (PDF, 1.71 MB) sets out effective controls for a range of common construction and manufacturing tasks.

If workers are using the controls recommended in the controls table for that task, and make sure they are using them correctly, you can be certain on reasonable grounds that the workplace exposure standard has not been exceeded.

Air monitoring should be undertaken by a person who has acquired the knowledge and skills to carry out the task, from training, qualification or experience.

Under the Managing respirable crystalline silica dust exposure in construction and manufacturing of construction elements Code of Practice 2022 (PDF, 1.71 MB), only a certified occupational hygienist (or a recognised equivalent competency under an international certification scheme e.g., certified industrial hygienist) is qualified to develop a sampling plan and to interpret the results.

Visit the Australian Institute of Occupational Hygienists to find a certified occupational hygienist.

An occupational hygiene technician is qualified to conduct personal exposure monitoring at the workplace.

Health monitoring

You must ensure health monitoring is provided to workers who are carrying out ongoing work using, handling, generating or storing RCS and there is a significant risk to the worker's health because of exposure. Further guidance on determining significant risk can be found in Safe Work Australia's Health Monitoring for exposure to hazardous chemicals - Guide for persons conducting a business or undertaking.

The Managing respirable crystalline silica dust exposure in construction and manufacturing of construction elements Code of Practice 2022 (PDF, 1.71 MB) provides a clear definition of when there is significant risk to a worker’s health.

From 1 May 2023, use this definition to work out if and when health monitoring must be provided to workers.

Keeping records:

All air monitoring results and health monitoring reports must be kept for a period of 30 years after the record is made.

Resources

WHSQ guidance:

- Fit-testing requirements for tight-fitting respirators (PDF, 0.86 MB)

- Work-related respiratory diseases

- Health monitoring

- Silica and the lung (PDF, 0.66 MB)

- Selecting the right portable extractor or industrial vacuum cleaner for hazardous dusts (PDF, 0.62 MB)

WHSQ reports:

- Tunnelling road header and related operations: dust conditions and their control (PDF, 0.15 MB)

- Tunnelling road header operations: dust conditions and their control (summary report) (PDF, 0.1 MB)

Safe Work Australia guidance:

- Crystalline silica - Hazardous Chemicals Requiring Health Monitoring

- Health monitoring when you work with hazardous chemicals guide

- Health monitoring for persons conducting a business or undertaking guide

Australian Institute of Occupational Hygienists (AIOH) Guidance:

- Australian Institute of Occupational Hygienists (AIOH) Position Paper on Respirable Crystalline Silica

- Find an occupational hygienist